Writing

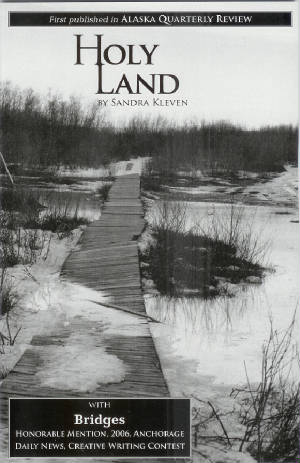

Holy Land

A Note to the people of

Bethel and the Delta

Published in The Delta Discovery, 2007

by Sandy Kleven

If

you pick up the new issue of Alaska Quarterly Review, and go to page 221, you

will find these words, “I will take you to a place I used to be. I will take

you for no reason. I can tell you nothing. I have no story. I don’t even

want to go there myself.”

This

grim invitation opens a dramatic monolog called “Holy Land.” I wrote

it. It’s about Bethel. I want

to tell you how I came to write it and

why I waited eight years to publish it.

Bethel

has shaped my life in both profound and mundane ways. Last time I moved away someone

said, “Once a

river rat, always a river rat.” I’ve

started to tell people that I never really leave. Bethel has left a mark on me.

The

drama continues, “So...how do we begin this story you refuse to hear? Should

we start this tale of winter here, on this broad reach of river gone to ice”“

I

type from memory. I open the text to

check it, not fully confident.

When

I left Bethel the first time, in 1987, stories were stirring, drums were

drumming and my dreams kept waking me. I did not think I would ever go back to

Bethel. When, in “Holy Land” I write, “This is our store. I see it in dreams,”

I really mean it. I was living in Washington State and my dreams were haunted

by the Alaska Commercial Company.

“Holy

Land” finally began to “speak” to me in 1996. Once I began to

write, the voice changed. It wasn’t me, anymore. It

was someone talking to me. The voice was confronting me and all of us “Gussaqs”

who come to Bethel from Outside “bringing your brains in a briefcase with

school papers for your wall to show us that someone thinks you’re smart.”

The

voice was mad and frustrated. He was sad

and disappointed. He had a wry sense of

humor. He was forgiving and loving. I

liked him. I don’t think he’s a real person, or the ghost

of someone real, but he could be. He

should have a name. I’d like to know

what to call him. He is a Yup”ik man

about 45 years old, weary with life. By

the story’s end he seems powerful, somehow transformed by experience. He

says, “Wherever you go you will hear me

calling. My spirit hand will lace through your entrails. I will squeeze and

whisper “Do you remember me now?”

He

says “I will reach for those places touched by my stories when you stood

shivering in dark rooms your heart as pliant as grass. I will reclaim the part

of you that belong now to us.”

He

is describing what happens to many who come to Bethel from elsewhere. We are shaped

by the experience. In a best-case scenario, we are made better

people. This is what I was trying to capture in “Holy Land;” the way the region

can transform the transplants.

When

it was finished in 1997, I didn’t have the nerve to send it off. I questioned

myself. How

could I pretend to speak for a Yup”ik Eskimo man? I had to bring the piece

before Bethel’s native

people.

I

moved back to Bethel in 1998. I begin to

read in to people individually or in small groups. Their response helped me feel

confident that

the piece was authentic. In the spring

of 2004, at Just Desserts, a Bethel talent show, I read a large part of it for

an audience of several hundred people. The

audience appeared to fully embrace the piece. One person said, “It’s

about time somebody

said all that.”

Only

then, eight years after Holy Land surfaced in my mind, could I submit it. Alaska

Quarterly Review accepted it right away. The editor Ron Spatz said that the

piece had generated excitement. It was

published in June of 2005.

“Holy

Land” is a stark piece of writing. It is unflinching, as it faces hard facts,

but

the best part of “Holy Land” is the challenge leveled toward the pilgrims drawn

to the Holy Land. It asks for sacrifice.

You are welcome, all right. More than

that, you will never get away. And

all that is asked of you is everything.

Since then, I published “Holy Land” as a book, in small

runs of 100 copies. Four hundred copies

have sold, through my limited efforts, largely in Bethel. So far, I have been

the only one to bring up

the question of writing in Alaska native persona. I think this is because the

writing is drawn

from what I have heard said by the people of Bethel. It is a writing of witness,

in that way. Still, the issue is a very serious one.

Had I failed to properly record what I heard,

if I had been off target, it would have violated the integrity of the

people. That is why it had to be heard

by the people I was depicting, to give me the assurance that, in their opinion,

it was proper. One response, years

later, showed me a different impact of the piece. A woman in a Yukon village

wiped away tears,

and said, “I didn’t think a white person could know how we felt.”

I have written other pieces in persona because I

hear native voices speaking. I like the

way these voices use English, cutting to the bone of meaning, while restrained

emotion makes what is said shimmer with significance. I restrain myself

because when I put these

words on paper, I am on holy ground. My

feet have to be bare and clean hands must delicately engage this sacred

task.